Technology and policy shifts will have big impacts on driving over the course of the 2020s. During this time, automated systems will achieve their biggest impact by helping to make humans better drivers rather than by taking over the driving task themselves. Electric vehicles are also coming—a major transition for the fleet.

In addition, the way we pay for infrastructure could be changing, as policymakers look at congestion pricing and other possible replacements for the gas tax. And although the big bipartisan infrastructure bill was signed into law back in November, it may take a few years to see the fruits of individual projects.

Automation: Evolution, Not Revolution

When most people think about automated vehicles (AVs), they tend to picture a future where cars simply drive themselves, with the humans on board sitting there like passengers in a taxi. That future may eventually happen, but most of us probably won’t see it before 2030.

More relevant right now are advanced driver assist systems (ADAS)—a broad category that captures several different kinds of systems. Currently being developed and deployed by automakers, they include features like lane-keeper assist, automatic emergency braking and advanced cruise control.

Policymaker response to these systems varies as much as the systems themselves. Lane-keeper assist has been widely embraced and likely has already saved lives by preventing crashes. Automatic emergency braking (AEB) is the top regulatory priority for automation at the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). NHTSA is currently developing a regulatory mandate to require AEB in all new cars, though it may take several years for a new rule to be finalized.

The type of ADAS under the most scrutiny is advanced cruise control. Such systems, including Tesla’s Autopilot program, cover a wide range of capabilities. Most are relatively modest and simply maintain speed, as with traditional cruise control, but are also able to automatically reduce speed when the vehicle is behind a slower-moving vehicle traveling in the same lane. Other versions are closer to what self-driving vehicles may eventually become.

In a shift from both the Obama and Trump administrations, the Biden administration is more closely scrutinizing the performance of these vehicles. In June 2021, NHTSA issued a Standing General Order requiring companies to submit a wide range of data on vehicles operating in any sort of autonomous mode. Safety advocates, as well as advocates concerned about potential job losses from automated vehicles, have applauded the order, hoping it will cause companies to proceed carefully when deploying or even testing these new technologies.

Surveys suggest a degree of skepticism as well among the general public about self-driving cars, and there have been several fatal crashes involving these vehicles. There are also concerns about the marketing of some of the systems—particularly relevant to dealers—that may promise more “self-drive” than the systems are prepared to deliver at present. While ADAS do indeed hold the potential to save lives, this is likely to be an uncertain decade as these technologies are adopted.

EVs: Prepare for a Major Transition

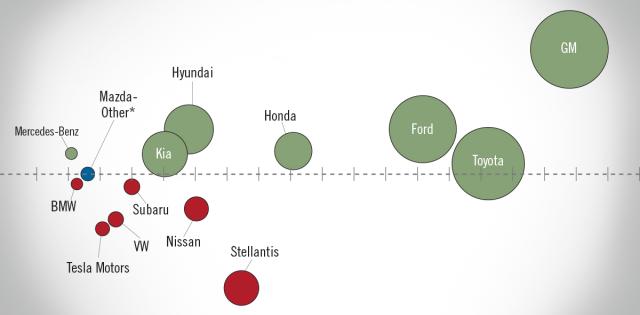

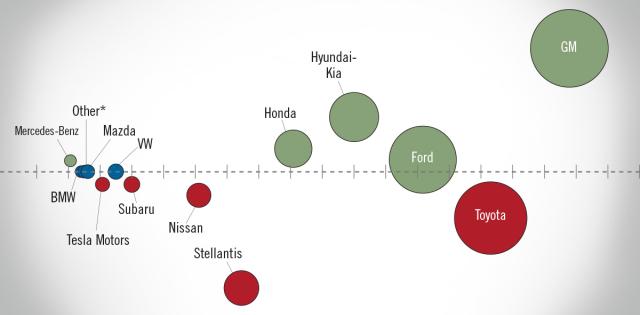

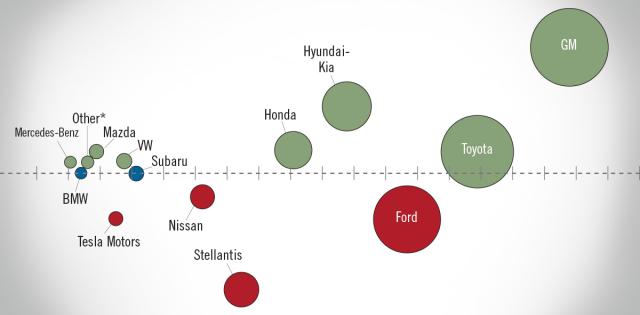

It seems more or less locked in that the U.S. fleet will be moving from gasoline toward electric in the coming decade. Policy support from the federal government and automaker declarations all point in this direction.

But what is the timeline and what does adoption look like? Several important challenges lie ahead for policymakers and companies:

- Charging infrastructure. EV charging infrastructure is being built out fast, with additional support from tax incentives and government grants. The perception of too few charging stations and where to find them persists, but this should fade in time—especially as charging stations, particularly with fast chargers, become more common.

- Grid power. If the entire U.S. fleet switches over from gas to electric, the grid will need to produce substantially more power. A Department of Energy study suggests that by 2050, demand on the grid will surge by 38%, much of it driven by EVs. While this is a challenge, there is no reason to believe the grid will not evolve to meet demand—as it has done so many times in the past, for example, with the dramatic increase of energy usage because of air conditioning in the 1950s. As long as the transition to EVs does not happen overnight, this will likely be overcome.

- Retooling and retraining. Dealerships everywhere are making significant investments in equipment and human capital. Automakers are moving quickly to pledge commitments to EV production, but the changeover will impose some costs.

- Consumer preference. Consumers are beginning to embrace EVs in larger numbers, so companies all along the supply chain need to be ready to adapt as automakers change over their product offerings and consumer uptake accelerates.

All of these challenges can, and almost certainly will, be surmounted as the fleet evolves—though speed of progress will vary.

Infrastructure: How We Pay for Roads

President Biden signed the new infrastructure bill into law back in November. Unfortunately for motorists, the infrastructure projects themselves will take some time, but we could see some major changes in how we pay for roads as a result of the bill.

Expect congestion pricing to be gradually adopted in key corridors. New York, for example, is currently developing an important test case. The U.S. Department of Transportation will also be running a voluntary pilot program on a vehicle- miles-traveled (VMT) tax, since the government will need an alternative to the gas tax as EVs begin to replace gas-powered cars. Expect this to be a major topic of debate by 2025 or so. A VMT tax is controversial, as it may threaten consumer privacy, and amounts to double taxation alongside the gas tax.

Meanwhile, money has to be issued from federal agencies to state and local officials for infrastructure projects, competition for funding has to play out, and the permitting process itself is a complicated beast. So don’t expect major progress on projects for the next year or two.

Ultimately, new techniques and new technologies, along with the incremental increase in funding, should produce better roads and improve the driving experience. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) continues to develop the Proven Safety Countermeasures Initiative, which stresses better turn lanes, rumble strips and other best practices for road management. The FHWA is also updating its Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, likely adding technology elements to road construction guidelines.

Permitting reform to enable faster project approvals should also be a priority. The new infrastructure bill for the first time puts into law the One Federal Decision concept, which will attempt to streamline the way multiple agencies obtain jurisdiction to review the environmental impact of projects. Yet this is an incremental step, since the U.S. is the hardest country in the world to build infrastructure in, for various reasons, and it is likely to remain frustrating.

Climate policy is also likely to evolve toward greater resilience against extreme weather conditions in infrastructure projects. While this will be less visible to dealers, it should reduce the risk of bridges and other infrastructure getting forced out of service or worse, such as the Pittsburgh bridge collapse earlier this year.

The 2020s are presenting U.S. transportation policy with a variety of changes and challenges. But with planning and foresight, policymakers from all political stripes can rise to the occasion.

Loren Smith is president of Skyline Policy Risk Group and former deputy assistant secretary for policy at the Department of Transportation.